Before Art "Superman" Pennington's career in professional baseball, he was a Hot Springs resident and attended Langston High School.

After playing around the United States and in Latin America, he settled in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where, at the age of 93, he died Jan. 4.

A funeral service will be held there today to remember him, both as a baseball player and person.

Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., spoke to The Sentinel-Record about Pennington, who he was able to spend time with over the years.

"He was a delightful man. I enjoyed our various encounters, whether it was at Negro Leagues celebrations or during his many trips to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum," Kendrick said.

What will stay with Kendrick most is Pennington's disposition and personality, along with how much he loved playing the game and talking about that time of his life.

He saw Pennington last in 2015, and although the player was slowing down, Kendrick still saw the twinkle in his eye when he would start talking about the game.

Arthur David Pennington was born May 18, 1923, and although his parents lived in Hot Springs, his mother had taken a trip to Memphis, Tenn., and went into labor while there visiting her sister, said his cousin, Linda Pennington Black, who resides in Hot Springs Village.

Local baseball historian Mark Blaeuer said of Pennington's early days, "When he was here in Hot Springs, he played on the same local team as his father for awhile, a team called the Highland Giants. They played at a ball field on Grove Street called Highland Park."

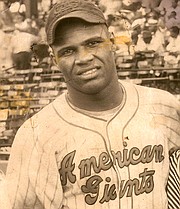

At age 17, after barnstorming around the South, he signed with the Negro Leagues' Chicago American Giants. As part of that team, he was a standout, being selected to play in the East/West All-Star Game three times.

In 1946, he was offered significantly more pay to take his skills outside the United States, playing in Mexico, Venezuela, Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

His cousin recalled him telling her that he even played against Fidel Castro while in Cuba, adding, "He enjoyed playing down there because there was no racial tension. He only came back to the United States after Jackie Robinson went into the Major Leagues, because he thought he might have a chance."

But, as Blaeuer pointed out, "Not everything changed all at once when Jackie Robinson crossed the color line," as some teams were open to interracial play, but many were not.

Black said she isn't sure her cousin would have been able to stand up to the pressure of enduring the treatment sure to have besieged him by members of the public at that time, especially since he had married a woman who wasn't black, and she wasn't even able to stay in the same hotel as he when traveling for games in the Minors.

Blaeuer said Pennington was treated badly because of his marriage, and that fact "may have been something that kind of kept him down," since his baseball play was outstanding.

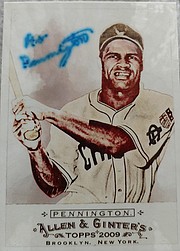

"He was truly a major league quality player," Blaeuer said, and noted that famed baseballer Sal "The Barber" Maglie referred to Pennington as "another Mickey Mantle."

Pennington had a lifetime batting average of .336 in his eight years in the Negro Leagues, won a batting championship one year while in the Minors, and got a home run hit on pitcher Dizzy Dean.

Black related a story her cousin told her, saying that when the Major League came to get Hank Aaron, Aaron couldn't believe it and told Pennington, "I don't know why they picked me, when they should have picked you."

Other greats Pennington played with include Jackie Robinson, Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, and his close friend, Roy Campanella.

Kendrick said Pennington talked about "how well they were treated when they were playing in Latin America," which shined a light toward the deficits in American society regarding racial relations.

Referring to Pennington and other black players in the 1940s and '50s, Kendrick said, "In their own respects, they were all champions of civil rights just by what they were able to endure to keep playing ball. And that fighting and prevailing spirit would ultimately pave the way for men who look like them to play in the Major Leagues."

While living in Cedar Rapids, Pennington continued to champion civil rights, opening the Home Run Club in 1963, which was the city's first integrated restaurant. He also ran for offices there, including sheriff, mayor and safety commissioner. He lost each one, but, according to the website baseball-reference.com, he said, "I knew I wasn't going to win, but I just liked to go out there and tell them about (prejudice)."

Black never knew about her baseball playing cousin until she began research for a book she was writing on Negro Leagues player William "Youngblood" McCrary. She saw the name Pennington, did some searching, and was finally able to meet him about three years ago, for which she is grateful.

She said Pennington's longtime caregiver and manager, Billy Valencia, has expressed an interest in planning a memorial tribute in Hot Springs in the coming months.

Kendrick said of the Negro Leagues players, "Every time we lose one of them, we feel like we're losing an extended part of our family."

Of Pennington, Kendrick said he "was one of the players who demonstrated that it's so much easier to love than it is to hate," and the way to keep him alive is to remember him.

Images of Pennington can be seen at the Kansas City museum, and he has a plaque along the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail.

As Kendrick pointed out, "When you learn the history of the Negro Leagues, you're learning the history of this country."

Local on 01/11/2017