EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the final installment of a multipart series on opioids, considered to be the fastest-growing abused substance in Garland County by local health officials.

Quapaw House Director Casey Bright says that stopping the rise of opioid abuse in Garland County comes down to entities holding the public to a higher standard of accountability.

Bright says it will take a multifaceted plan to properly address the opioid crisis on both a national and a local level, with law enforcement personnel and medical practitioners on the front lines in the fight.

Bright said Arkansas has done well in the area of prevention and prescription drug take-backs, but is "way behind" in providing a variety of treatment methods for cases of opioid addiction. He said he hopes an annual grant of $3.5 million for the "state-targeted response to opioid treatment" that has been obtained by Arkansas will help with that.

Law enforcement officials say Arkansas also needs to make progress in preparing officers for dealing with opioid overdoses. In a presentation at the Prescription Drug Summit Nov. 9 at the Hot Springs Convention Center, Stan Jones, a Drug Enforcement Agency special agent from Nashville, said Arkansas trails other states in this initiative.

"You're gonna see more treatment of it," Bright said. "The question still remains if people are convinced from a social setting that they need treatment and are willing to accept it."

Preparing law

enforcement

Bright said that, with the grant, a number of law enforcement personnel will be given Narcan, a counter-agent for opioid overdoses, to treat suspected overdoses. Hot Springs Police Chief Jason Stachey said he hopes to provide all of his officers with Narcan in the form of nasal spray by spring 2018.

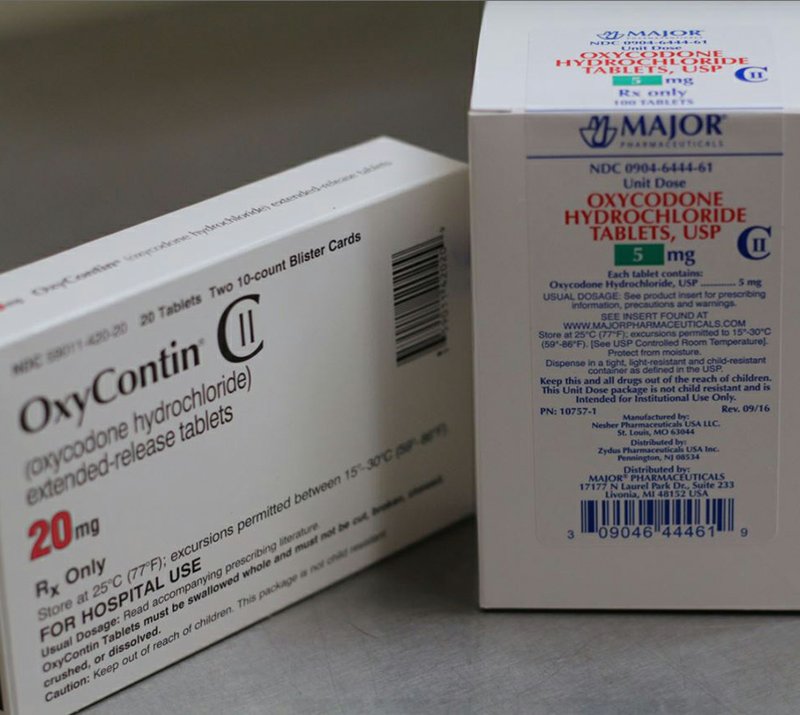

"A lot of times, our police officers are the first on scene at any kind of overdose," he said. "If they have reason to believe that that individual has overdosed on some kind of opioid product, whether it's hydrocodone, OxyContin or heroin, they can administer this nasal spray, and it will begin immediately deterring the effects of that drug."

Jones said Narcan is "for everyone involved" at the scene. He noted that law enforcement, medical personnel and firefighters who are working a scene are at risk of deadly opioids like fentanyl that can be absorbed into the human body through the eyes, mucus membranes, sinus cavities, mouth or skin.

Jones also said law enforcement agencies now need to be careful when operating drug busts. He gave the example of a SWAT team in Connecticut that detonated a diversionary device in a fentanyl lab and made the fentanyl go airborne, landing everyone on the team in the hospital.

Jones said Garland County is not exempt from the illegal manufacture of fentanyl.

"We need to get away from the idea that it only happens in big cities," he said. "This is happening here."

Bright said law enforcement officials need to pay attention to people who have overdosed after they have left the hospital. Stachey said that while his department does pay attention to social issues like opioid abuse, such a duty should not fall on the shoulders of law enforcement.

However, Stachey did say he agrees with Bright's idea, stating that "maybe a group or organization works with the hospital" to provide further treatment after an individual who overdosed is treated.

"I do believe there needs to be some kind of contact and some kind of follow-up," Stachey said.

Preparing doctors

Though prescribed opioid recipients per 10,000 people and quantity dispensed per capita have decreased steadily for most monitored substances in the county since 2014, the amount of oxycodone dispensed per capita has increased steadily from 2014 to 2016, according to the Arkansas Prescription Monitoring Program. The latest available data shows Garland County's rate of oxycodone dispensed to be 15-18 per capita in 2016.

The PMP state survey shows that Garland County was in the top half of Arkansas counties in reference to amount of oxycodone and hydrocodone, both per capita and number of recipients of these substances per 10,000 people, in 2016.

Dr. James Tucker, general surgeon for Surgery Specialists of Hot Springs, says most of the opioid epidemic is by street versions of the medications.

"The PMP state database is required to be used for any prescription postoperative, and the data on the PMP website clearly shows rates are constant and/or decreasing," Tucker said.

"The other issue is that narcotics are so commonplace, and the truth of the matter is that they are being manufactured on the street, and therefore untraceable. Most of the epidemic is by street versions of the medications. There is a mass production of non-pharmaceutical grade medications being shipped to this country that is not being monitored. Every narcotic from a drug company that is administered to a pharmacy and delivered to a patient via a doctor's prescription is accounted for."

Asked how doctors can prevent abuse, Tucker said, "Our priority as physicians is to provide the best quality care to every patient which at times includes treatment and prescriptions for sports, work and traumatic injury as well as surgical and postoperative care. It's our job to make a clinical judgment on the duration and dosage for the treatment of pain. There are multiple factors in play and we consider multi-modality pain therapy to ensure the best treatment and the lowest risk for each individual patient."

As far as how often doctors in Garland County overprescribe, Tucker said over-prescription of drugs would "again be individualized according to the data on the PMP, because unfortunately in that scenario, you're going to have caregivers who prescribe a lot of pain medicine because their primary role as a caregiver may be chronic pain. General surgeons and orthopedic surgeons are going to have a high rate of pain medication for postoperative patients, as well."

One way to ensure doctors don't overprescribe is "technological monitoring, first and foremost, which is in process with the Prescription Monitoring Program," Tucker said.

"I think that any and all patients that require more than 30 days of pain medication should be referred to a pain specialist. Our office policy is that anybody who requires more than 30 days of pain medication after surgery has to be transitioned to a chronic pain specialist. The other is pain contracts. I believe that a lot of practitioners need to look at pain contracts where the pain medications come from one prescriber. Patients with complex medical conditions really only need to have their medications come from one prescriber, the person with the pain contract," Tucker said.

Along these lines, Bright recommends that doctors openly ask patients about their potential addiction to pain medications.

"If you think that's a possibility, don't be afraid to communicate with them," he said. "If they get upset because you brought it up, there more than likely is an issue, and you probably should stop prescribing."

Bright said that in prescribing therapy, doctors should cross-check the records of patients who are asking for prescriptions.

"It's, 'I'm in step three and they're still in pain, so I'm gonna start back over and I'm gonna allow them to be prescribed this for a longer period of time.' Well, no. Evidence shows that they should be better," he said. "The next follow-up would be, 'I'm gonna give you a 30-day prescription, but I need to see the records from your physical therapist. I need to see some record of how you're progressing and what they're seeing."

Local on 11/19/2017