EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the first in a series of articles about some of the Major League legends who once trained in Hot Springs by baseball historian Bill Jenkinson, in conjunction with the inaugural Hot Springs Baseball Weekend.

In a time when Major League Baseball has acknowledged an epidemic of "sore arms," consider the fantastic success achieved by professional pitchers in the early 20th century who trained in Hot Springs.

We don't know with certainty why it happened. They all hiked or ran over the local mountain trails. They all took the hot baths. Many of them played a lot of baseball in town. Some played golf while others didn't. Some visited the casinos and horse races while others chose not to. Frankly, it's a bit of a mystery. Yet, beginning with John Clarkson in 1886 (possibly even sooner) and continuing until Major League pitchers stopped coming to Hot Springs over a half-century later, there was a record of phenomenal success for those who trained in Hot Springs. For the record, Clarkson won 328 games in his Hall of Fame career.

There is even some evidence that Charles "Old Hoss" Radbourn came to town in 1881 after injuring his right throwing shoulder the preceding season. According to those accounts, Radbourn retired from the game and went home to work as a butcher. He was then convinced to come to the Spa City, and give it one last try. Why is this tale important?

We know that Charles Radbourn played his first full Major League season in 1881 when he won 25 games for Providence. He went on to win a total of 309, including an absolutely mind-numbing 59 games in 1884. Those numbers, however incredible, are real. Did it all happen because Old Hoss came to Hot Springs in 1881?

Let's look at the roll call of pitchers who later came to town, and eventually became legends. The list is extraordinary, so let's select a few of the most romanticized individuals, starting with one of the earliest and certainly one of the all-time best.

Cy Young

In his historic 22 years in the Major Leagues, Cy Young established almost every record for durability. That includes his most-ever 511 wins and most-ever 316 losses. It also entails his all-time record 7,356 innings-pitched. In today's game, Big League teams hope that their starting pitchers throw 200 innings in a season. In five different years, Young exceeded 400 innings, and, in 11 other seasons, he topped 300. He threw every imaginable breaking ball, whereas the modern guys are dissuaded from tossing pitches, which create high levels of stress on their arms. So, pitch selection is not the explanation for Young's unique durability.

This we do know: Young trained in "The Valley of the Vapors" in, at least, 13 different years. He hiked and jogged relentlessly over the rugged mountain trails, thereby achieving high levels of cardiovascular fitness. In the process, he also significantly increased his leg strength. For those who don't understand that reference, all modern pitching coaches advocate the development of strong legs. Why? The more they "push off" with their legs from the pitcher's mound, the less strain is placed on their arms.

Plus, during all those visits to The Valley, Young was also regularly "taking the baths." The combination of the mountain training along with the therapeutic hot baths worked wonders.

Also, consider this: Young visited Hot Springs for the first time in 1892, his third Big League season. During his stay in the Valley, he pitched in five exhibition games against the Chicago White Stockings (now known as the Cubs). That was his so-called breakout year, posting a 36 and 12 record while accruing a 1.93 ERA. In that same remarkable season, Young hurled the astonishing total of 453 innings. Was it a coincidence that he achieved such historic success after training for the first time in Hot Springs?

Along with those astonishing innings pitched, Young naturally accrued some equally amazing pitch counts. Official pitch counts were not kept in those days, but in recent years some baseball-oriented mathematicians have used computer science to create highly reliable formulas for estimating the number of pitches thrown. By combining batters faced, bases-on-balls, and strikeouts, they cross-checked with modern known pitch counts to establish their guidelines. Since all those statistics are available to everyone online, once the formulas became available, making the calculations was a relatively easy process. The formulaic results are almost always within a few pitches (more or less) of the official totals.

By today's standards, any single game pitch-count exceeding 130 is considered exceptional. In Young's case, probably the best example of his astounding stamina occurred on the Fourth of July in 1905. Pitching in Boston versus the Philadelphia Athletics' iconic Rube Waddell (another Hot Springs trainee), Young hurled 20 innings during a heart-wrenching complete game loss to his talented, but eccentric, rival. In that historic confrontation, Young threw approximately 257 pitches!

In 1908, as Young turned 41, he understood better than anyone that he was approaching the end of his pitching days. Accordingly, he returned to Hot Springs for pre-spring training, and continued to do so for five straight years. As late as May 4, 1910, at age 43, Young pitched a 14-inning 3-3 tie in St. Louis. Along the way, he tossed about 210 pitches.

Just contemplate that for a moment: a 43-year-old man throwing over 200 pitches in a Major League game! Despite the common perception that modern athletes are more physically advanced than their predecessors, no contemporary hurler could even consider attempting what Cy Young did. He is the ultimate symbol of a pitcher who became a legend by training in Hot Springs.

Walter Johnson

Despite enjoying a highly successful season in 1910 (25 wins and 17 losses), Walter Johnson got off to a slow start. That had been the case each year, starting in 1907 when he made his Major League debut. Johnson knew full well about Hot Springs as a result of his interaction with the older Cy Young. Accordingly, young Johnson journeyed to the Valley of the Vapors in February 1911. He went there to get into peak physical condition, and he did. Johnson pitched very little in Hot Springs, but he did hike the mountain trails and take the hot baths. He even played some very competitive baseball.

So many Major Leaguers were training in the Valley that preseason, that there were enough to organize a kind of All-Star Game. On both Feb. 23 and 24, while playing right field for the American League Stars against their National League rivals, Johnson clubbed long home runs. The second of those two, launched at Majestic Park, soared so far to center field that Johnson, who was regarded as the mightiest hitter in MLB until Babe Ruth came along, declared it the longest drive of his career. He went on to record an even better mark of 25 and 13 in 1911, and credited much of his success to his early spring work in Hot Springs.

Although vowing to return to the Valley, the "Big Train" was so dominant over the next decade that he just didn't find the time to come back. That all ended in 1920 when he suffered the first serious "sore arm" of his career. He dropped precipitously to an 8 and 10 record while pitching a measly (for him) 143.2 innings. That induced Johnson to finally return to the Valley in early 1921, and he was glad that he did. At age 33, he bounced back with a 17-win season while hurling 120 more innings than the year before.

He only waited three more years this time to return, and the results were historically dramatic. After suffering from some leg problems in 1923, Johnson did a lot of hunting and hiking in the Reno, Nev., area during the following winter. He then used his influence with the Washington Senators' owner and new manager, Bucky Harris, to send many of the team veterans to pre-spring training in Hot Springs. Up to that time, the Senators had never won the American League pennant in their 22-year history.

In his definitive biography, "WALTER JOHNSON: Baseball's Big Train," historian Henry W. Thomas wrote: "At Hot Springs, even before the formal start of spring training, a spirit of camaraderie developed among the regulars. ... They worked out together, took marathon hikes in the Arkansas hills, enjoyed the 'radio-active' baths, and played cards with one another."

Specifically, on the matter of conditioning, Thomas had this to say: "The legs causing so much trouble in 1923 had been built up and strengthened, and it was Johnson who set the pace for the rest of the team in their daily treks in the foothills of the Ozarks around Hot Springs. 'The Mountain Goat,' they started calling him. 'He had most of us staggering around until we became accustomed to the uphill going,' Bucky Harris recalled. 'We returned to Tampa (formal spring training site) in fine condition.' A report from Hot Springs noted that 'When some of the party return (from the mountain hikes) tired and ready to call it a day, Walter rests by playing from 18 to 36 holes of golf.'"

The results were astounding. The 36-year-old Johnson posted a 23 and 7 record while leading the traditionally inept Washington Senators to not only their first American League pennant but the World Series championship, as well.

Johnson trained again in Hot Springs in early 1925 and very nearly reprised his amazing accomplishments from a year earlier. He began by "warming up" on the front lawn of the grand Eastman Hotel on Feb. 25, 1925, as the other hotel guests gasped in awe at his still imposing fastball. Johnson accrued a 20 and 7 record as the Senators claimed their second straight AL pennant. That autumn, they lost the World Series, but their two-year run, starting both times in Hot Springs, was the best-ever for the franchise. The Valley of the Vapors had worked wonders for both the team and its legendary best player.

When you closely examine the factual history of Johnson's visits to Hot Springs, it appears that he only came when he needed help the most. That somewhat odd pattern would be repeated by others.

Smoky Joe Wood

Smoky Joe Wood is one of the most intriguing players in baseball history. Born Howard Ellsworth Wood in Kansas City, Mo., in 1889, Wood's beloved father was a gifted but adventurous fellow. He rambled across the country to pursue whatever career fantasy motivated him at any given time. As a result, Wood's youth was divided between western Kansas, south Chicago, eastern Pennsylvania, and frontier Colorado. It was a nomadic and challenging childhood, but it imbued young Wood with an inner toughness which would serve him well throughout his own eventful life.

Wood developed a passion for baseball at an early age and participated wherever he lived. In 1905 and 1906, he played respectively for his so-called town teams in Ouray, Colo., and Ness City, Kan. Oddly, Wood finished that 1906 season by playing for a few weeks as one of four males on a primarily female team known as the National Bloomer Girls (based in Kansas City). That was not uncommon in those days.

Wood then spent his first professional season with the Class-C Hutchinson (Kansas) Salt Packers where he permanently switched from the infield to the pitcher's mound. Moving rapidly upward, Wood next joined the Class-A Kansas City Blues in 1908. Despite a losing record, he threw so hard and so effectively that the Boston Red Sox purchased his contract in late August. Within two years, Wood, at age 20, was a Major League star. Two years after that, relying mostly on his astonishing velocity, Wood performed at a level that has never been surpassed in baseball annals.

After training in Hot Springs in 1912, Wood went on to compile an extraordinary 34 and 5 record while posting a dazzling 1.91 ERA. During that historic season, Wood also hurled 344 innings and threw 35 complete games along with 10 shutouts. Amazingly, he finished this magical year by winning three more games while vanquishing Christy Mathewson and his New York Giants in the World Series.

That season is the centerpiece in the still-enduring legend of Smoky Joe Wood. How could it not be? No human being has ever pitched better than Wood did in 1912. That was also the year when the word "smoky" was attached to the front of his name.

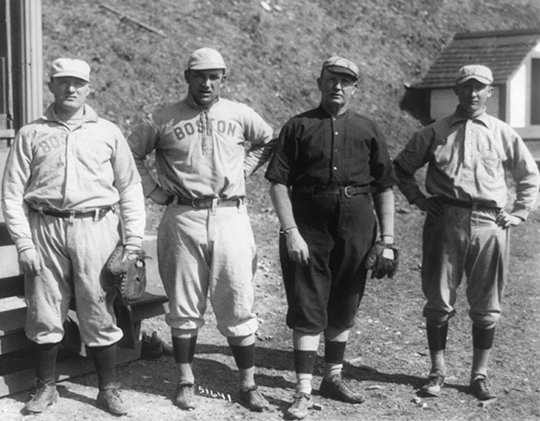

Despite rumors that he may have pitched too much the preceding year, when Wood and his Boston teammates returned to Hot Springs for spring training in 1913, he was on top of the athletic world. On March 28 that year, Wood took the mound for an exhibition game against the immortal Honus Wagner and the Pittsburgh Pirates at Whittington Park. Throwing fastballs which could hardly be seen by the naked eye, Wood shut out the Pirates over five innings. During that time, he struck out seven, including Wagner himself on two occasions.

In that moment, Smoky Joe Wood was on his way to possibly becoming the greatest pitcher in baseball history. However, as it often does, fate intervened. While pitching in Philadelphia on April 21, Wood injured his thumb sliding into second base. He missed the next three weeks before returning ineffectively in Detroit. He lasted only two innings in relief; it was obvious that he just wasn't ready to pitch. And yet, Wood was the starting pitcher three days later in St. Louis (May 15, 1913).

For some unknown reason, despite clobbering the Browns 15-4, Manager Jake Stahl allowed his injured ace to throw a complete nine-inning game. In the process, Wood threw approximately 159 pitches. Such obvious overuse (bordering on abuse) would not be tolerated today, but, back in that primal baseball era, it was not unusual.

Focusing on this point, during Wood's next nine starts, he averaged 155 pitches and 9.2 innings per start (including consecutive 12 inning complete games). It is theorized that, during this entire time, Wood altered his delivery to compensate for his lingering thumb injury. As a result, his priceless right shoulder was being worn to an anatomical frazzle.

If that wasn't bad enough, he then slipped on wet grass while fielding a ground ball in Detroit on July 18. Nearly incredibly, he fell on the same, already damaged, right thumb, this time causing a serious fracture. Trying to rehabilitate, Wood pitched two meaningless innings in September, but that was it for 1913.

When Wood married Laura O'Shea near his ancestral home in Pennsylvania on Dec. 20, 1913, he was thought to have suffered ptomaine poisoning during the post-ceremony reception. Hoping to enjoy his honeymoon, he didn't seek further medical treatment. Sadly, that misdiagnosis led to even more problems. In the early morning hours on Feb. 22, 1914, doctors rushed to his house and performed an emergency appendectomy on his kitchen table. In the process, they saved his life, barely, but those events led to another compromised season.

Wood carried on for another year as a starting pitcher and was highly effective when on the mound. Yet, the pain was constant, and he never pitched more than 157 innings after 1912. In 1915, after returning to Hot Springs again, he amassed an outstanding 15 and 5 record. He also led the American League with an eye-popping 1.49 ERA. However, by that time, his right shoulder was so badly damaged that pitching had devolved into pure agony. In all likelihood, he was suffering from a torn rotator cuff. At age 25, Smoky Joe Wood was, essentially, finished as a pitcher.

Wood resurfaced a few years later as a converted outfielder with the Cleveland Indians. There he joined best friend and fellow Hot Springs devotee Tris Speaker. As late as 1922, Wood was playing All-Star caliber baseball with Cleveland in his adopted position. That year, he batted .297, scored 74 runs, and drove in 92. Miraculously, considering his shoulder ailment, the 32-year-old marvel even managed to record 18 assists from his spot in right field.

Wood could have played for a few more years, but, when offered a baseball coach's job at Yale University, he accepted. Within a year, he was the head coach and kept that position until 1942. Despite his earlier health problems, Wood lived to the advanced age of 95, enjoying life to the end. He never forgot his time in the Valley of the Vapors. He suffered a lot of adversity during his athletic career, but not in Hot Springs. By hiking the mountain trails and taking the hot baths (even playing some memorable games), he rose to the top of the baseball world. He didn't stay there long, but his legend remains.

Bill Jenkinson, of Willow Grove, Pa., was one of the historians involved with the research and development of the Hot Springs Baseball Trail, along with Mike Dugan, Mark Blaeuer, Don Duren and Tim Reid. All of the baseball historians contributed to this article.

Local on 03/20/2018