Jan. 12 falls on a Sunday this year, as it did in 1969 when it became a watershed date in sports history.

Eight days before Richard Nixon, twice beaten for political office earlier in the decade, became the United States' 37th president, Joe Willie Namath engineered a Truman beats Dewey-like upset that rocked professional football.

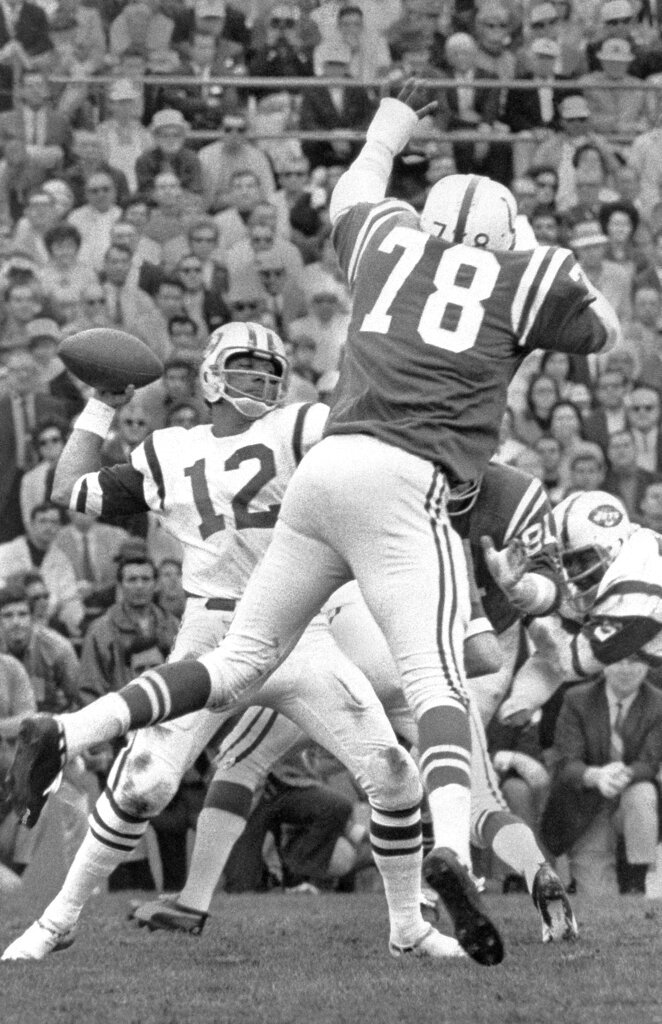

Then the National Football League's most flamboyant player, one who liked his women blonde and Johnnie Walker Red (or so he said), Namath backed up a midweek boast concerning Super Bowl III. Guaranteeing a victory over the highly favored Baltimore Colts, the long-haired kid from Pennsylvania who played college football at Alabama under Bear Bryant, led the New York Jets to a 16-7 victory at the second Miami Super Bowl in three years.

To anyone who wasn't around then, the outcome may not seem all that surprising. Why wouldn't a team with Joe Namath, he of the bad knees but quick release, not have a big game? The first pro quarterback with a 4,000-yard season, Namath spoke honestly, he thought, that veteran Earl Morrall, his opposite number with the Colts, could not match up with some rival QBs in the American Football League.

Namath only voiced in public what his teammates were saying after watching the Colts on film. That even with the great Bubba Smith anchoring the line, the Colts' defense, especially the pass rush, wasn't any more ferocious than, say, of the Oakland Raiders, whom the Jets beat in the AFL championship game. Perhaps falling for his pretty-boy image, the Colts were lulled to sleep by a quarterback whose knees were shot but whose knack of reading defenses was extraordinary and whose pocket presence rivaled that of an aging Johnny Unitas on the other side. If the Colts wanted to blitz him, let them, Namath said.

Other quarterbacks have had splashier days in the Super Bowl than Namath, who in his one appearance completed 17 of 28 passes for 206 yards. Succeeding two-time winner Bart Starr, Namath was the first Super Bowl MVP without scoring or throwing for a touchdown.

Not that there were not other candidates. Matt Snell, the Jets' bruising fullback, ran for the game's only TD -- one of his 30 carries for 121 yards -- and George Sauer Jr., who didn't catch many passes at Texas for Darrell Royal, had eight receptions for 133 yards. Those were Super Bowl records, as were the two interceptions by Jet defensive back Randy Beverly and the three picks (of the Colts' four) by Morrall.

In retrospect, Namath received MVP honors that day more for intangibles than performance. But whatever the voters had in mind, they made absolutely the right choice. Broadway Joe never got close to the Super Bowl again, but on Jan. 12, 1969, he was the winning quarterback in a landmark game that helped define professional football as the nation's No. 1 spectator sport.

Namath sometimes gets too much credit for the victory, specifically that he was responsible for the AFL-NFL merger in 1970. That came about largely after the AFL, in the spirit of maverick Raiders owner and new Commissioner Al Davis, declared war on the NFL, offering huge contracts to veteran players in hope they would jump leagues once their current deals expired. The NFL was ready to negotiate after Wellington Mara, owner of the New York Giants, defying a "gentleman's agreement" not to poach players from the other league, signed Buffalo kicker Pete Gogolak.

In June 1966, one month after Gogolak signed with the Giants, the leagues agreed to merge four years later and stage a common draft. One byproduct was that the AFL and NFL winners would meet to determine a true world champion in what would become the Super Bowl.

The Green Bay Packers, coached by Vince Lombardi, for whom the Super Bowl championship trophy would be named after his death in 1970, dominated the Kansas City Chiefs and Oakland Raiders, respectively, when it was called merely the AFL-NFL Championship game. Having crushed the Cleveland Browns 34-0 for the 1968 NFL title, the Colts went off against the Jets as heavier favorites (18 points) than either Packer team against the AFL champion.

But in a game closer on the scoreboard than on the Orange Bowl grass, the Jets scored first, Snell going over in the first quarter, and added three Jim Turner field goals. Unitas, the old master, came on, a sore-armed legend replacing a scatter-armed one, and his touchdown pass with 3:19 left averted a shutout.

To those playing in the game or watching in the stands or at home on NBC, the outcome was absolutely staggering. To some of us, it still is.

"Leaving the field, I saw the Colts were exhausted and in a state of shock," said Snell. "I don't remember any Colt coming over to congratulate me."

In an iconic photo, Namath is shown leaving the field with his right index finger extended, signaling "number one." He and Neil Armstrong, who six months later would become the first man to walk on the moon, and John Wayne, playing a one-eyed sheriff (Rooster Cogburn) in "True Grit," were some of 1969's biggest heroes.

In a game fraught with irony, Jets coach Weeb Ewbank gained revenge against the franchise that fired him despite two NFL titles with the Colts. Cornerback Johnny Sample, another ex-Colt, collected one of the Jets' four interceptions. On the other side, Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom held the loss against Don Shula, who coached one more year in Baltimore before turning the Miami Dolphins, an AFL expansion team, into a two-time Super Bowl champion.

After the merger, Namath would outduel Unitas in a regular-season game when both were in the twilight of their careers. Sadly, both are remembered for playing out the string with other teams, Unitas wearing the uniform of the San Diego Chargers and Namath, younger than Unitas but looking older, that of the Los Angeles Rams.

Namath, to no one's real surprise, was not named recently one of the NFL's top six quarterbacks in the league's first 100 years. Some debate whether he belongs in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, a point that I argued at length (on Namath's side) one day in a college dorm.

What I remember is that along with Muhammad Ali, Joe Namath ranks among the most charismatic athletes of his time. Like Ali in declaring which round an opponent would fall, Namath elevated what came to be known as trash talking with his Super Bowl guarantee. Call the Super Bowl his 15 minutes of fame, if you wish, but the afterglow from that January Sunday in 1969 extends to this day.

He wasn't much of an on-screen actor (no Oscar nominations for 1970's "Norwood") and, one night when drunk on the sidelines at an NFL game, embarrassed himself before ESPN interviewer Suzy Kolber. Namath briefly retired from football in 1969 before divesting himself of interest in a Manhattan bar, Bachelors III, that the NFL guessed was home to unsavory customers. He was no choir boy in college, Bear Bryant suspending him from a Sugar Bowl.

But in 1965, his rookie contract, $427,000 over three years, sounded like $40 million. And no one looked better in a mink coat or panty hose, bad knees and all, or wearing No. 12 (not even Tom Brady) than Joe Willie Namath.

Sports on 01/12/2020