“Garland County is the worst in the state in whiskey stills,” announced Major D. Keating of the State Police during the middle of Prohibition. He continued, “In fact, I’ll go further and say it is the worst in the south.”

Bootlegging (moonshining) had gone into high gear in Garland County when the Constitution’s 18th Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, became law in 1919. Hot Springs’ 31 saloons closed their doors, and the thirsty called on bootleggers, who operated in almost all areas of the county. From Jessieville, Beaudry, and the Dark Corner area in the northeast to the Little Mazarn in the west, and from Ragweed Valley in the west to Lonsdale and Price Station in the east and the Jack Mountain area of the south, dozens of lazily curling smoke columns revealed the locations of stills. In the Buckville area, even a Baptist minister was convicted of moonshining. One apparently typical Garland County man explained why he made bootleg liquor: “Well, everybody out our way is doin’ it.”

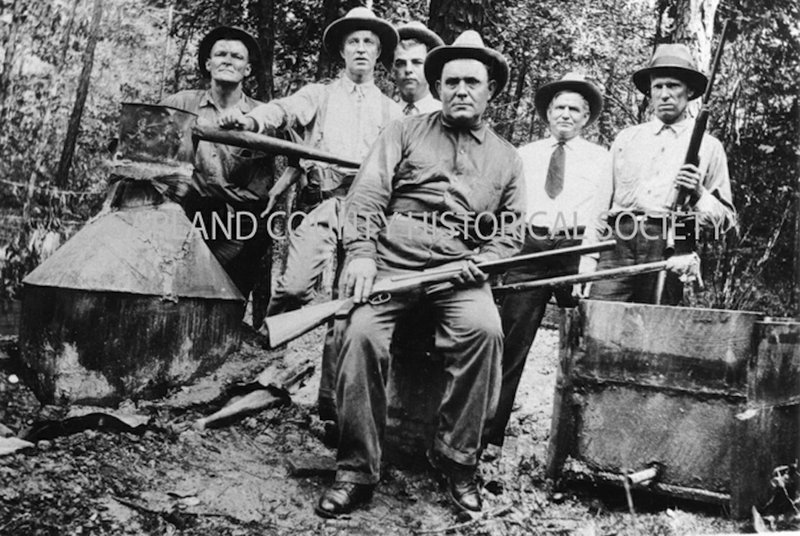

Enforcing the law against moonshining was difficult, although arrests increased after the government offered rewards for turning in stills and bootleggers. In 1925, 1,293 violators of the liquor laws were arrested in Garland County, 84 stills were smashed, and 39,100 pounds of sugar to be used in mash were destroyed. The hunt for bootleggers was dangerous. Lawmen and moonshiners here were killed or wounded, but not even violence could stop the illegal production. A New Orleans newspaper commented that the corn and grain market in Arkansas was being calculated by buyers by the gallon instead of by the bushel.

Moonshiners were inventive. In a ravine between rural Shady Grove Road and Gulpha Creek, officers found a steel burial casket serving as the pot of a moonshine distilling plant. Also off Shady Grove Road, officers discovered a still hidden in a hollow log after following several drunk and staggering hogs to its location.

But bootlegging wasn’t confined to rural areas. People in Hot Springs were making home brew on cook stoves, mixing gin in their bath tubs, and cooking mash in their garages. The sexton of Greenwood Cemetery professed to be surprised when a mourner, placing flowers on a grave, discovered a still in the back area of the graveyard.

According to historian Orval Allbritton, an unexpected consequence of moonshining was the effective end of the Ku Klux Klan in Garland County. In that era the Klan aggressively opposed bootlegging. In 1922, 30 robed and hooded members of the local Klan burst into a Wednesday night church meeting in Lonsdale and warned the attendees against bootlegging. The next night, five car loads of Hot Springs Klan members planned to deliver the same message at a Jessieville area school, where people were watching a movie. Three moonshiners, however, ambushed the Klan outside the school. One Klan member was killed and two wounded. The episode shocked the people of Hot Springs, and Klan membership quickly dwindled away.

Prohibition ended in 1933. Prohibition, though, did not mark the beginning of bootlegging in Garland County and Prohibition’s abolition did not mark the end of bootlegging here. But after Prohibition, perhaps Garland County was no longer “the worst in the south.”

Time Tour is a monthly history feature provided courtesy of the Garland County Historical Society. For more information, GCHS may be contacted by email at [email protected] or phone at 501-321-2159.