EDITOR'S NOTE: Pro Football Hall of Famer Bobby Mitchell, a Hot Springs native, died Sunday at the age of 84. The following are excerpts from "The Remarkable Bobby Mitchell" by historian Don Duren, originally published in the 2011 edition of The Record, the annual publication of the Garland County Historical Society. A complete version of the article is available at hotsr.com.

Bobby Mitchell won fame as a professional football player who played for the Cleveland Browns and the Washington Redskins. In 1983, the professional football committee selected him as a member of the National Football League Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Long before his professional career began, however, Mitchell was a star in his hometown. Mitchell, born in Hot Springs, was a standout athlete at Langston High School in Hot Springs, graduating in the class of 1954.

Although Hot Springs newspapers The Sentinel-Record and The New Era would refer to the Langston four-sport standout by his given name, Cornelius Mitchell, his family called him "Neal." Neal (Robert Cornelius Mitchell) was born in Hot Springs, Ark., on June 6, 1935, to Albert and Avis Mitchell. His father was a minister, and his mother was a homemaker. A bi-vocational pastor, his father worked during the week at one of the bath houses owned by the National Park Service on "Million Dollar Bathhouse Row" in downtown Hot Springs.

A middle child in a family of eight children, Mitchell attended Goldstein Elementary School and played baseball, basketball, and football with neighborhood friends. He recalled, "My older brother didn't want me around, and my younger brother was too young. It's maybe why I turned to sports." People soon noticed his speed, ability, agility and versatility.

Growing up in Hot Springs, Mitchell met and became friends with several professional players who visited the Spa City during their offseason. Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Monte Irvin were among the major league baseball players who stayed at one of the of the few black-owned hotels in the city (probably the National Baptist Hotel). Mitchell noted, "For black players, Hot Springs was like their spring training since they weren't welcome in Florida. We were very fortunate because we got a chance to play baseball and basketball with all these great people." He also said, "We got to know these guys personally. It was a great situation for all of the young kids. To grow up in an area like that was a great advantage for someone like me." When he graduated from Langston in 1954, Bobby wore a suit purchased for him by Campanella.

By the time Mitchell graduated from high school, he was a star. Local newspapers called him "Mr. Touchdown." His childhood friend and high school and college teammate Charles Butler once said, "Nobody could catch him. He was a threat to break loose on anything. He was hard to get your hands on because he had the instincts to shift his feet. A lot of times we would have plays where they were supposed to go through the tackles, but he bounced outside, and he was so quick that he could pull it off."

Little Rock Dunbar graduate Sidney Williams, who attended the University of Wisconsin and became the first black quarterback to start in the Big Ten Conference, remembered playing against Mitchell: "He was a guy who got out of seemingly impossible situations."

In 1952, (Mitchell's) junior year in high school, he scored 23 touchdowns. An injury sidelined Mitchell in the third quarter of the last game of 1952, as Langston lost the state championship to Jones High School of North Little Rock. Mitchell, however, received the first of many honors as he was chosen to the All-State squad.

Langston, with a student enrollment of only around 300 from the seventh to 12th grades, was a small school compared to most of the schools they played. But the senior-packed 1953 version of the Langston High Bulldogs was very talented. In an early season game, Langston triumphed over a much larger school, the Bossier City Bears of Louisiana, 48-7 as Mitchell rambled for three TDs. Cornelius "Mr. Touchdown" Mitchell scored three touchdowns against Little Rock's Dunbar High School, as Langston rolled to a 37-7 triumph.

An injury slowed Mitchell for a few games, but he came back with a vengeance against Washington High of El Dorado. El Dorado player Prince Holiday recalls, "We were shaking hands with him before the game and he said, 'You better enjoy this because it will be the last time you touch me tonight.'" The Langston Bulldogs trounced the Oil Town team 48-2 as Mitchell romped for three more six pointers.

Fort Smith's Lincoln High School was Langston's next target. If the Bulldogs won their last game of the season, they would be state champions. "Langston Batters Ft. Smith To Win State Championship" was the headline in The Sentinel-Record on Nov. 28, 1953. In front of 1,200 fans at Rix Stadium in Hot Springs, Langston smothered Fort Smith 61-6 to cop the Negro Big-Eight state football crown. Langston finished the season with a record of 9-2. The two losses were at the hands of large, out-of-state, all boy schools -- Melrose High of Memphis and Manual Training School in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Mitchell garnered All-State honors for the second year.

Now it was decision time for Mitchell. Should he give professional baseball a whirl or play college football and track? Since he had several college scholarship offers, should he stay close to home or head to unknown areas?

The St. Louis Cardinals offered him a baseball contract. He considered the offer, but he was troubled by the experience of a friend. In 1954, his good friend Uvoyd Reynolds, the quarterback of the Langston Bulldogs, signed with a farm team of the St. Louis Cardinals, the Hot Springs Bathers in the Class C, Cotton States League. (He was the first black player signed by the Bathers.) Reynolds played for a month or so, but didn’t make the grade. Mitchell thought Reynolds was an awesome baseball player, and he doubted that he could hook up with a professional baseball team if someone as talented as Reynolds didn’t made it to the majors.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Unfortunately, however, very few black athletes attended “white” colleges in the South for many years after that ruling. Mitchell considered several schools, including Coach Eddie Robinson’s Tigers at Grambling University in Louisiana, an all-black school. Grambling would be relatively close to home. A University of Arkansas alumnus approached Bobby about playing for the Hogs. Mitchell would have lived off campus with a “nice colored family.” If the offer had panned out and if Mitchell had accepted it, he would have become the first black football player at the University of Arkansas.

A year earlier, his good friend and high school teammate Charles Butler had received a football scholarship to the University of Illinois, thanks to Hot Springs Attorney Henry Britt. An Illini graduate, Britt had asked an Illinois coach to visit Butler and Mitchell at the Spa City during Butler's senior year (which was Mitchell's junior year). Britt knew the two Hot Springs players were good college prospects, and the Illini coach was duly impressed with their abilities. Butler urged Mitchell to accept Illinois' scholarship offer. Butler had a big influence on Mitchell's decision, but his mother had a bigger influence. Fortunately, his mother and his friend were of one mind. She voted for Illinois, so Mitchell chose to head to Champaign where Butler, his former high school teammate, played.

In Illinois, Mitchell encountered racial discrimination to a degree that he had not known before. He has stated that racial discrimination was seldom a big ordeal in Hot Springs, that blacks had rights in Hot Springs that others outside Hot Springs didn't enjoy.

"I rave about Hot Springs," he said in a 2011 interview. "I tell people, 'Everybody lived the same.' I don't even remember riding on the back of the bus. Maybe I did. But Hot Springs was different from most of Arkansas. People came there from all over the country for the baths. But I knew that 20 miles from Hot Springs I'd be hurt."

Attracting over a million tourists annually, Hot Springs’ citizens were accustomed to working with all races and cultures. Some individuals looked on Hot Springs as more “cosmopolitan” as compared to many cities in the South. In 1953, the Hot Springs Bathers, now owned by a group headed by A. Gabe Crawford, Louis Goltz, and Henry Britt, wanted to play black players on their professional baseball team (seven years after Jackie Robinson became the first black player in the major leagues). The president of the Cotton States League objected. He said that Hot Springs was “too cosmopolitan” to understand how the rest of the South felt about blacks and whites playing together and that signing black players would stir up a “hornet’s nest.” In 1954, the Bathers nevertheless signed their first African-Americans player, Mitchell’s friend Uvoyd Reynolds.

Leaving the segregated South, Mitchell arrived at the University of Illinois in Champaign and found more discrimination that he had known in his hometown. Black players, for example, lived off campus in old Army barracks, while white players lived in the dorms. He was not comfortable with this atmosphere. Also, since NCAA freshmen athletes couldn’t play on varsity teams during the 1950s, the first year was practice time for all freshmen. During his first two years at Illinois, Mitchell was ready to pack his bags and head back to Hot Springs.

However, All-American halfback J. C. Caroline was an inspiration to Mitchell and other black athletes. Caroline encouraged the black athletes to stay in school at Illinois. Then at the beginning of Mitchell’s junior year, the college dean asked Mitchell to become the first black to move into an all-white dorm. It was another, better world in the dorm. From then on, Mitchell felt that he was a part of the school.

Beginning in his sophomore year, halfback Mitchell was second team, listed behind Harry Jefferson. On Dad’s Day, the seventh game of the season, Saturday, November 4, 1955, the high-flying Michigan Wolverines invaded Memorial Stadium on the Fighting Illini campus. With the score tied 6-6 in the third quarter, Jefferson went down with an injury. Enter Bob Mitchell. Before 58,968 fans, the former Langston Bulldog went to work. He took a handoff and scampered fifty-five yards to set up the go-ahead touchdown. With 9:45 left in the game, Mitchell outran the entire Wolverine team as he tallied on a sixty-four-yard jaunt for a 19-6 Illinois lead. His teammates carried an exhausted Mitchell off the field. With six minutes left, Illinois intercepted a Michigan desperation pass, and a few plays later the Illini crossed the goal again to make it a 25-6 score. Coach Ray Eliot let Mitchell relax during the last six minutes of the game. He had earned a rest. Mitchell’s statistics at the end of the game totaled 184 yards, including one touchdown.

What did the papers say about his feat? “His entire performance was accomplished in little more than 20 minutes.” After entering the game in the third period, “Mitchell proceeded to give one of the greatest individual shows seen in Memorial Stadium since the days of ‘Red’ Grange.” The paper stated that the 25-6 win was the largest margin of victory over a Michigan team since Red Grange ran wild in 1924. “Mitchell was like a star falling out of heaven.”

What did “The Galloping Ghost,” Red Grange, say about the man from Hot Springs? “Where did Ray (Coach Eliot) come up with that guy?” Grange continued, “I guess there’s another one coming on to pass my rushing record.” It was a tremendous compliment coming from Harold “Red” Grange, one of the greatest players who ever played college football. Following the game, an Illinois newspaper’s headlines in the sports section screamed, “Illini and New Whiz Stun Michigan 25 to 6 . . . Mitchell in Gala Day . . . 184 Yards!”

After the Wisconsin game, the newspaper headlines told the story: “Mitchell Paces Illinois Over Wisconsin, 17-14.” The fleet-footed halfback had run for two touchdowns and hipped his way for thirty-nine yards to set up the game-winning field goal. It was a quick sophomore year, but it was a good start to a promising college career.

A knee injury in 1956 marred Mitchell’s junior year. He worked hard rehabilitating the knee for his 1957 senior season. Mitchell, however, was losing his enthusiasm for football, although he believed the people around him probably didn’t realize it. He continued to play well on offense and defense during his senior season, and he was chosen to the 1958 All Big-Ten Team.

By the spring of 1958, Bobby was eager to run track. It seemed that track came naturally to him. Since he hadn’t participated in a track event since high school, however, he was not sure how track was going to work out. In 1958, he caught on fast. He established an indoor world record in the 70-yard low hurdles with a time of 7.7 seconds. Unfortunately, the record lasted only six days.

At an indoor track meet in Cleveland, Coach Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns came out to watch Mitchell run. He performed well that day, and in the spring of 1958, he led Illinois to the Big 10 Track Championship by collecting thirteen individual points. Mitchell tied Wilmer Fowler in the 100-yard dash at 9.6 seconds. He came back and won the 200-yard dash in 21.3 seconds. In addition, he landed over twenty-four feet in the long jump. The coaches selected Mitchell to the All Big-Ten track team. Is it any wonder, as the 1960 Rome Olympics approached, he began contemplating running for the United States Olympic Team?

Mitchell graduated from the University of Illinois with B.S. degree in physical education in the spring of 1958. He then joined the 1958 College All-Stars as they played the NFL’s 1957 champions, the Detroit Lions. The Lions were thirteen-point favorites as 70,000-football fans jammed Chicago’s landmark Soldier Field.

In the second quarter, the College All-Stars, behind 7-0, got untracked as Billy Joe Conrad of Texas A&M kicked a 19-yard field goal. Later in the quarter, the All-Stars jumped on the scoreboard by way of an aerial from quarterback Jim Ninowski of Michigan State to Mitchell. The play covered eighty-four yards and put the All-Stars in the lead 10-7. “Strike while the iron is hot,” someone said. The Stars did just that. In the same quarter, the identical combination of Ninowski to Mitchell scored on an eighteen-yard pass. A third quarter safety by Bill Jobko of Ohio State and an interception of Layne’s throw by West Virginia’s guard Chuck Howley iced the contest for the All-Stars 35-13. Bobby Joe Conrad had kicked four field goals for the Stars. Ninowski and Mitchell earned co-MVP honors.

At Illinois, Mitchell had met his future wife, Gwen Morrow of Charlotte, North Carolina, who was also a student at the university. The couple married in May 1958, and Mitchell has said that marriage was the best move he ever made. Not long after his marriage, he was surprised when the Cleveland Browns picked him in the seventh round of the 1958 NFL draft because he thought the pros wouldn’t give him a second look. When Coach Paul Brown of the Browns offered the athlete a $7,000 contract, thinking of his family responsibilities, he decided to give up his Olympic dream and sign a pro football contract.

In 1958, Coach Brown positioned Mitchell at halfback, next to the great fullback, Jim Brown. The tandem worked so well together that reporters called them “Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside.” That year, Del Shofner of the Los Angeles Rams, Mitchell, and Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns, “distinguished themselves by scoring twice in a game from long distance.” The flashy Mitchell soared over the Eagles by scoring on a 98-yarder for a TD. Later, he dashed sixty-nine yards on a punt return for another six points. Against the St. Louis Cardinals, the 6 foot 192-pounder tacked on another TD with a dazzling 63-yard scamper from scrimmage. Prior to the end of the season, many sportswriters predicted Brown and Mitchell would be named “Most Valuable Player” and “Rookie of the Year,” respectively.

The sportswriters were correct—the December 24, 1958, issue of The Sporting News headlined, “Player Prizes to Brown, Mitchell in Another Sweep for Cleveland.” Hal Lebovitz, an award-winning sports columnist, wrote, “Fullback Jimmy Brown and Halfback Bobby Mitchell, teammates on the Cleveland Browns, are the respective winners of The Sporting News-Marlboro Player of the Year and Rookie of the Year awards in the National Football League.” Coach Brown noted that his twenty-three-year-old freshman halfback scored six touchdowns: “His long-shot running in several games was responsible for putting us in the playoffs. Everybody thinks of him as a great sprinter and he is. But more than that, he has unusual balance.”

At the end of the 1958 season, the Browns tied the New York Giants for first place in the Eastern Division of the NFL with 9-3 season records. However, the Giants defeated the Browns 10-0 in the Eastern Division playoffs to gain the right to play the Baltimore Colts in the championship game. In “the greatest game ever played,” the Colts beat the Giants 23-17 in overtime.

As the 1959 season rolled around, Mitchell again played well. On November 11, he set a club record for the longest run from scrimmage with a 90-yard blast, as the Browns took care of the Redskins 31-17. It was also the longest run from scrimmage in the NFL that year. During the 1959 season, due to his speed, he was nicknamed “Mitchell the Missile.” In 1960, “the Missile” was selected to the Pro Bowl.

In 1958, Mitchell joined the Army National Guard, and in 1961, they came knocking on his door, literally. After the first three games of the season, Mitchell received a phone call stating that he was summoned into active military service because of the Berlin Crisis. He recalled, “I thought it was a joke and told my wife there was some nut on the phone. About an hour later, there was a knock at the door, and the man told me I would have to leave for Fort Meade [in Maryland] the next day. I called Paul Brown, and he said I had to go and he reminded me that he didn’t have to pay me if I was in the military. I was crying. We had just bought this new house, and I didn’t know what we were going to do.”

Fortunately, Mitchell’s drill sergeant let him leave on the weekends to play football: “I’d get there Saturday morning, find out what the game plan was, and play the game the next day.” In that 1961 season, Mitchell rushed 101 times for 548 yards and five touchdowns and caught 32 passes for 368 yards. Mitchell served in the National Guard from 1958 to 1968.

Following the 1961 season, the Browns traded Mitchell to the Washington Redskins, as Washington became the last NFL team to integrate. The Kennedy administration had forced Redskins owner George Preston Marshall to integrate by using the non-discrimination clause in the stadium lease agreement that Marshall had signed with the Interior Department, the proprietor of the Washington stadium. If Marshall did not integrate the Redskins, the government, owners of the stadium, could deny the team the use of DC Stadium (later named RFK Stadium).

Two other blacks joined the 1962 Redskins team, but Mitchell, the outstanding player among the three, was widely regarded as the one who integrated the Redskins. He went to Washington rather reluctantly. He had felt at home in Cleveland and had enjoyed playing for Coach Paul Brown. In addition, his role as “first one to integrate the Redskins” put him under great pressure from unwelcoming whites and from blacks who expected much from him. He recalled, “The Redskins owned the Atlantic seaboard at the time . . . there were no other teams [in the Atlantic area] at the time. Their white fans, particularly in North and South Carolina, Alabama and Florida, weren’t used to having a black player on their team. My first year was rather difficult . . . the comments we had to listen to. And there was a lot of pressure on me to perform. So many blacks were counting on me; they wanted me to be a Superman. It was difficult to play and make everybody happy.”

Since the Redskins had won only one game in 1961, Redskins Head Coach Bill McPeak, unlike many white Redskin fans, welcomed the new black players. The versatile Mitchell became a Washington flanker, the position he wanted to play. (Today, “flanker” is known as “wide receiver.”) In the first three games of the 1962 season, Mitchell snagged 16 aerials from quarterback Norm Snead for a total of 376 yards; five of the passes resulted in TDs. In those three games, he exceeded his total receiving numbers during an entire season with the Browns. The addition of Mitchell to the team took pressure off Snead as the high-flying Redskins won their first three games. “Bob Mitchell’s presence brought the ’Skins their most glorious triumph in ages when he helped defeat his former teammates at Cleveland, 17-16, on a 50-yard pass play with Snead . . . Snead and Mitchell are giving Washington its greatest battery since Walter Johnson and Gabby Street,” affirmed Washington sportswriter Jack Walsh.

In his first game as a Redskin during that 1962 season, Washington journeyed to the Cotton Bowl in Dallas. In the first quarter, Mitchell scored the first Washington touchdown on a six-yard pitch and catch from Snead. In the third quarter, the speedy Mitchell blazed his way to the end zone by returning a 92-yard kick-off. Snead and Mitchell weren’t finished. In the fourth quarter, the aerial circus continued as Snead laid the pigskin out in front of the flanker as they combined for an eighty-one-yard TD. The final score was Washington 35 and Dallas 35.

The next game was against his old team, the Browns. John Walsh related the facts about the last part of the Browns’ game: “So in the last ninety-six seconds, Mitchell turned one of the greatest 50-yard touchdown moves ever made on a football field to bring the Redskins home 17-16.” Mitchell moved in from his flanker position to the halfback spot. Snead called a pass-play designed for Mitchell to go deep. Linebacker Fiss bumped Mitchell off his intended route, so Mitchell adjusted and quickly settled for a short pass over the middle. He caught Snead’s pass and headed to the Browns’ sideline. Everybody knew he was heading out of bounds to stop the clock.

Linebacker Sam Tidmore and defensive back Jim Shofner had the correct angle to cut Mitchell off at the pass. “Suddenly, Mitchell gave his speeding pursuers a hesitation step that instinctively pulled them to their left. Mitchell put on a burst of speed to get away from them, turned a wicked corner two yards inbounds, and headed goalward,” Walsh wrote. Mitchell cut back toward the middle and got blocking help from his teammates. He outran another opponent as the defensive back “clutched air and Mitchell danced happily in the Cleveland end zone.” Redskins Coach McPeak said, “No other NFL player could have scored on that play.” Fans of Mitchell in Hot Springs were not surprised; they recalled his legendary “stutter-step” followed by his explosive “afterburner” when he played for Langston.

The 6 feet, 192-pound elusive flanker had a tremendous year for Washington in 1962. He gathered in seventy-two passes for a total receiving yardage of 1,384 yards as he hit pay dirt eleven times. Add a ninety-two-yard kick-off return for a TD, and Mitchell scored twelve times for a total of seventy-two points for the season. The high-stepping receiver ran for a combined season total of 1,794 yards. The Redskins, helped by Mitchell, won five games that year—a definite improvement over the one game they had won in 1961.

In 1963, the 28-year-old pass catcher readied himself for another year with the Redskins. Washington finished next to last in the Eastern Division, winning only three games. However, the Redskins had a potent passing attack as Mitchell led the Redskins’ receivers. It was Mitchell’s career year. In eight explosive games, he racked up yardage of 122, 98, 112, 173, 100, 218, 197 and 99. In addition, he added a 99-yard kick off return for a touchdown. In 1963, Mitchell had a career-high season of 1,852 total yards. Of that total, 1,436 yards were receiving yards.

In 1966, Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham became the new Redskins head coach. In that same year, Mitchell totaled 1,067 all-purpose yards, of which 905 yards were by the receiving route. He scored ten touchdowns. In 1967, he gained 866 yards via the passing attack, scored seven TDs, and accumulated a total of 1,055 yards. In 1968, Coach Graham moved Mitchell back to the running back position, where he had moderate success, and switched running back Charley Taylor to the flanker position. The Redskins finished third in the Capital Division in 1968. The Dallas Cowboys won the division with a 12-2 record, followed by the New York Giants, 7-7, the Redskins 5-9, and the Philadelphia Eagles 1-12, at the bottom of the pile.

When teams don’t win, coaches are usually the first to go, and Otto Graham was out as head coach in 1969. Vince Lombardi, the legendary coach of the Green Bay Packers, became the new Washington coach. He was eager to work with Mitchell at flanker in 1969. During training camp, however, Mitchell told Coach Lombardi that he believed that his 34-year-old legs were gone. He retired before the 1969 season began, believing that it was time to let the younger men take over.

Lombardi requested that Mitchell remain in the Redskins organization as a scout. Mitchell later graduated to the office of Assistant General Manager and served in that position until his retirement in 2003. In 1997, Mitchell described his role for the Redskins as a liaison between the players and owners. With a laugh, he said, “The coach comes in through one door, the owner through another, and I’ve got to stand between them.”

Mitchell’s big reception years were about every year. In 1960, he caught 45 passes, and he continued to catch over55 passes each year through the 1967 season. In 1962, leading the league, he caught 72 passes, in 1963, 69 passes, in 1964, 60 passes, in 1965, 60 passes, in 1966, 58 passes, and in 1967, 60 passes. From 1958 through 1968, Mitchell was on the receiving end of 521 passes, which equaled 7,954 yards. During his NFL career, he scored 91 touchdowns (including eight kick returns for TDs) and collected 14,078 total yards. Mitchell was a four-time Pro Bowl selection, once as a running back and three times as a wide receiver.

Mitchell and his wife, Gwen, who is an attorney, live in Washington, D. C., where they have been members of a local church for 40 years. Their son, Robert Cornelius, Jr., graduated from Stanford University and Georgetown Law School. Their daughter, Terri, graduated from Illinois in 1981 and later earned a master's degree from Howard University. Mitchell’s two favorite hobbies are fishing and playing golf.

Through the Bobby Mitchell Hall of Fame Golf Classic, which he started in 1980, Mitchell has helped raise nearly $7,000,000 for leukemia research. He has been associated with many other causes such as The Boys and Girls Club of Washington, D. C., The Urban League, the NAACP, the American Lung Association, the White House Task Force on Drugs, the United Negro College Fund, the Howard University Cancer Research Advisory Committee. Other organizations include the Washington Board of Trade, the Metropolitan Washington, D. C. Area Leadership Council, the Martin Luther King Holiday Commission, the Junior Chamber of Commerce, the University of Illinois Presidents Council, and the University of Illinois Foundation.

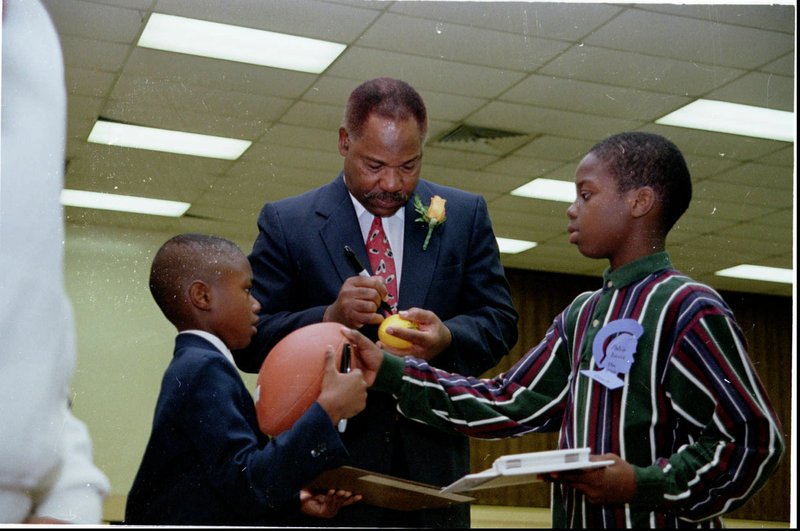

In 1977, Mitchell was selected to the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame and in 1997, Mitchell was inducted into the new Arkansas Walk of Fame in Hot Springs. During a visit home for the ceremony, he toured Langston Intermediate School, which named a gymnasium in his honor. He said, "I'm proud to say that I'm a graduate of Langston High School."

When asked about growing up in Hot Springs during segregation, he said: "I don't remember ever having a sad day in this town, as far as relationships are concerned. I had as many friends uptown as I had on the boulevard (his neighborhood). We all came together. That's why people from Hot Springs, no matter where they are, always talk about Hot Springs and are not afraid to say they're from Hot Springs. I'm proud, proud to say I'm from Hot Springs, Ark. This city means a lot to me."

His hometown is proud as well, proud of the outstanding athlete and fine man who grew up in Hot Springs, Ark.

Local on 04/07/2020